Fighting Fire with Automation

Scientists at NYU Tandon are innovating fire prevention with AI algorithms and scientific models. Swarms of fire-sensing robots may be next.

When wildfires scorched swaths of Los Angeles in January 2025, few should have been surprised. Over the preceding months, the Southern California region had become a tinderbox and was just a spark away from disaster.

A recent pair of remarkably wet winters had caused vegetation to flourish. But the fall of 2024 had seen record lows in precipitation, turning the plants into kindling. Roaring Santa Ana winds, which swept dry, hot air from California’s interior deserts towards the coast, rustled the vegetation and threatened to blow any potential flames out of control.

The spark finally came in early January. The resulting fires, which included some of the deadliest infernos in the state’s history, raged for nearly a month and destroyed some 7,000 structures. Initial estimations put the total damage at over $250 billion. More than 30 people lost their lives.

Attempting to contain wildfires once they reach this scale is a losing proposition. The only way to prevent tragedies like those that happened in Los Angeles is to get ahead of the risks and extinguish wildfires before they turn deadly. But continuously monitoring an environment’s fire risks and clearing vegetation is timeconsuming and expensive.

These constraints recently inspired several researchers at NYU Tandon to combine their expertise in fire behavior, risk assessment, optimization and robotics. Known as the Burn Risk Assessment and Hazard Mitigation through Automation initiative, or BRAHMA, the project aims to make wildfire monitoring and prevention feasible.

To do this, the team is integrating a variety of approaches and new technologies. “One of the big problems today in wildfire safety is that the tools exist, but a market to integrate them does not,” said Assistant Professor Augustin Guibaud (MAE), one of the BRAHMA researchers.

Guibaud and his collaborators plan to finally combine these existing tools like AI, data optimization and robotics to create novel solutions to wildfire prevention. Ultimately this work may create an automated fleet of devices that can detect fire risks and clear flammable vegetation around the clock

Augustin Guibaud

Augustin Guibaud

Firsthand Experience

As the principal investigator for NYU’s new IgNYte fire lab, Guibaud specializes in studying how fluid mechanics, heat transfer and chemistry explain fire behavior in complex environments. For example, he studies how flames flicker in low- to zero-gravity conditions by conducting experimental burns on parabolic flights, where a plane flies up and down in arcs to simulate space travel and create brief intervals of weightlessness.

He also studies the unique fire risk of historical buildings, including elaborate medieval cathedrals. Over the past three years, Guibaud served as an expert witness during an inquiry into the 2019 blaze that engulfed the wooden spire and timber-lined roof of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris.

But few blazes are as complex as wildfires, a natural disaster that incinerates the boundary between nature and the human world. “Wildfires are natural phenomena that many ecosystems rely on to thrive,” Guibaud said. “But when that fire gets in touch with human habitats, that’s when it becomes a disaster that’s difficult to control.”

To understand these threats, Guibaud utilizes a myriad of tools to model fire risks and scan vegetation cover. However, combining these approaches to assess wildfire risks is still relatively rare, which makes it difficult to understand just how vulnerable some areas can be.

Guibaud experienced this first hand in 2021 when he was tasked with assessing wildfire risks on Porquerolles, a Mediterranean island off of his native France. The idyllic isle presents a complex setting for fire safety—it is covered by a national park, which protects local wildlife and vegetation, and is home to a historic village and a pair of vineyards, which were introduced to the island as fire barriers and also attract tourists. The wine growers were particularly wary of potential flames.

“Even if it doesn’t burn, the vine is very good at capturing the particles,” from the surrounding environment, Guibaud said. “If there’s a wildfire, the wine is going to taste like smoke for the next decade.”

Yet despite the importance of preventing fire on Porquerolles, it had been several decades since a formal wildfire assessment was conducted on the island. The last assessment was not only outof-date from a science perspective but was also out of sync with the island’s current conditions. Over the decades, the island’s vegetation had become overgrown and unkempt, creating fuel for destructive fires. And with a growing number of tourists milling about Porquerolles, an errant cigarette sparking a dry shrub was a real risk.

As he crafted his updated report, Guibaud quickly discovered that maintaining the island’s vegetation over the years was costly and largely untenable. “Nature is going to regrow and change,” he said. “In our built environment, we can control everything. In nature we can’t.”

A Team Effort

Each of Guibaud’s collaborators in the BRAHMA initiative has had similar experiences tackling difficult problems in the real world. For example, Assistant Professor Yuki Miura (MAE, CUSP) assesses how cities like New York can become more resilient to climate-related threats like flooding.

In her research, Miura integrates physics models, climate science, AI, finance, and remote sensing with socioeconomic factors like population dynamics and economic activities to create accurate flood and other risk assessments to achieve effective risk management.

Yuki Muira

Yuki Muira

“Bringing these streams together allows me to not only simulate the hazard itself but also evaluate who and what is most at risk to eventually address the risks,” she said. Wildfires pose a much different risk than floods due to their ability to incinerate physical boundaries and spread in multiple directions. But Miura believes the interdisciplinary approach she has applied to raging torrents of water will also prove useful to understanding the impact of wildfire.

“The underlying challenge is the same—identifying, measuring, and managing risks under deep uncertainty,” she said. Miura plans to simulate fire hazards, measure how fires damage communities and infrastructure, and quantify long-term health and economic effects from cascading impacts that linger long after the fire’s embers are extinguished to help decision-making.

Tying these various threads of information together into a comprehensive approach will be difficult, but Assistant Professor Kimberly Villalobos Carballo (TMI) is up to the task. As part of her NYU work, Villalobos designs optimization models to finetune decision making in complex situations like healthcare. Ongoing efforts include streamlining one of the most stressful work environments in the world: the operating room. Using discrete optimization models, Villalobos synced up surgeries with surgeon and staff schedules and available resources to keep operating rooms running smoothly despite the logistical and personnel constraints many face every day.

Kimberly Villalobos Carballo

Kimberly Villalobos Carballo

Villalobos and the rest of the BRAHMA team believe these tools are also applicable when it comes to organizing disaster relief efforts and preventing wildfires. For example, the team is currently working on crafting a framework to finetune vegetation clearance strategies that reduce wildfire risk while balancing ecological and financial costs, workforce availability and environmental constraints. These strategies will be guided by advances in machine learning that combine diverse data sources—like satellite images, climate and weather histories and vegetation assessments—to build more accurate predictive models than ever before.

Villalobos stresses that these optimization strategies will also be influenced by those that know an area’s fire risks better than anyone: the local communities. She and the rest of the team think that hearing from these stakeholders will help calibrate BRAHMA’s tools for the real world, helping the team understand real-world constraints such as budget limits, workforce capacity and local environmental regulations.

“Prediction is only half the story,” Villalobos said. Once risks are identified, decisions must be made about how to allocate limited budgets to preventative measures, where to prioritize vegetation clearance, how to stage emergency stations or which evacuation routes will minimize congestion during a crisis. “That’s where optimization becomes essential: it provides rigorous frameworks to make the best possible decisions under real-world constraints,” she added.

Automating the Process

The BRAHMA team believes that automation will help make this vital, yet expensive and time consuming, work feasible. One potential route the team is exploring is to utilize drones and terrestrial robots as automated landscapers by pruning overgrown trees and clearing brush themselves.

This may sound like a science fiction vignette, but Institute Associate Professor Chen Feng (CUE, MAE, CSE, CUSP, C2SMART) thinks this goal is not quite as futuristic as it seems. The principal investigator of NYU’s AI4CE lab, founding co-director of NYU’s Center for Robotics and Embodied Intelligence, and another BRAHMA collaborator, Feng thinks that retrofitting robots for fire prevention will likely only take years instead of decades. “Even though people haven’t thought about using these technologies for fire prevention, much of the hardware is already there,” he said.

When Feng joined BRAHMA, it was his first foray into fire safety research. By trade, the roboticist specializes in developing the mapping, localization, and perception capabilities of robots. However, applying this research to wildfires felt like a natural fit.

“Superficially, it may not be very clear how my work in robotics is directly related to fire monitoring,” Feng said. “But if you think about it more closely, the fundamental research I work on in robotics, especially perception, navigation, and mapping, has obvious benefits for fire safety.”

Chen Feng

Chen Feng

In recent years, first responders have increasingly embraced the ability of robots to scope out dangerous disaster sites and keep tabs on both victims and rescuers. Feng recently participated in a contest held by the National Institute of Standards & Technology. His team designed a vision-based application that, using data from cameras and scanners, could quickly map an environment and track the locations of first responders in real time.

His work with BRAHMA will aim to apply some of that same technology to aid not only in disaster response but also in prevention. “We want to use robotics as more than just a data collection tool or a search and rescue tool,” Feng said. “This technology could be used potentially as a preventative tool.”

To accomplish this, Feng and the BRAHMA team plan to utilize drones and terrestrial robots to continuously monitor conditions in areas with high fire risks. The goal would be to outfit these devices with sensors to collect environmental data, which would be instantly uploaded to a cloud and sifted through by AI algorithms.

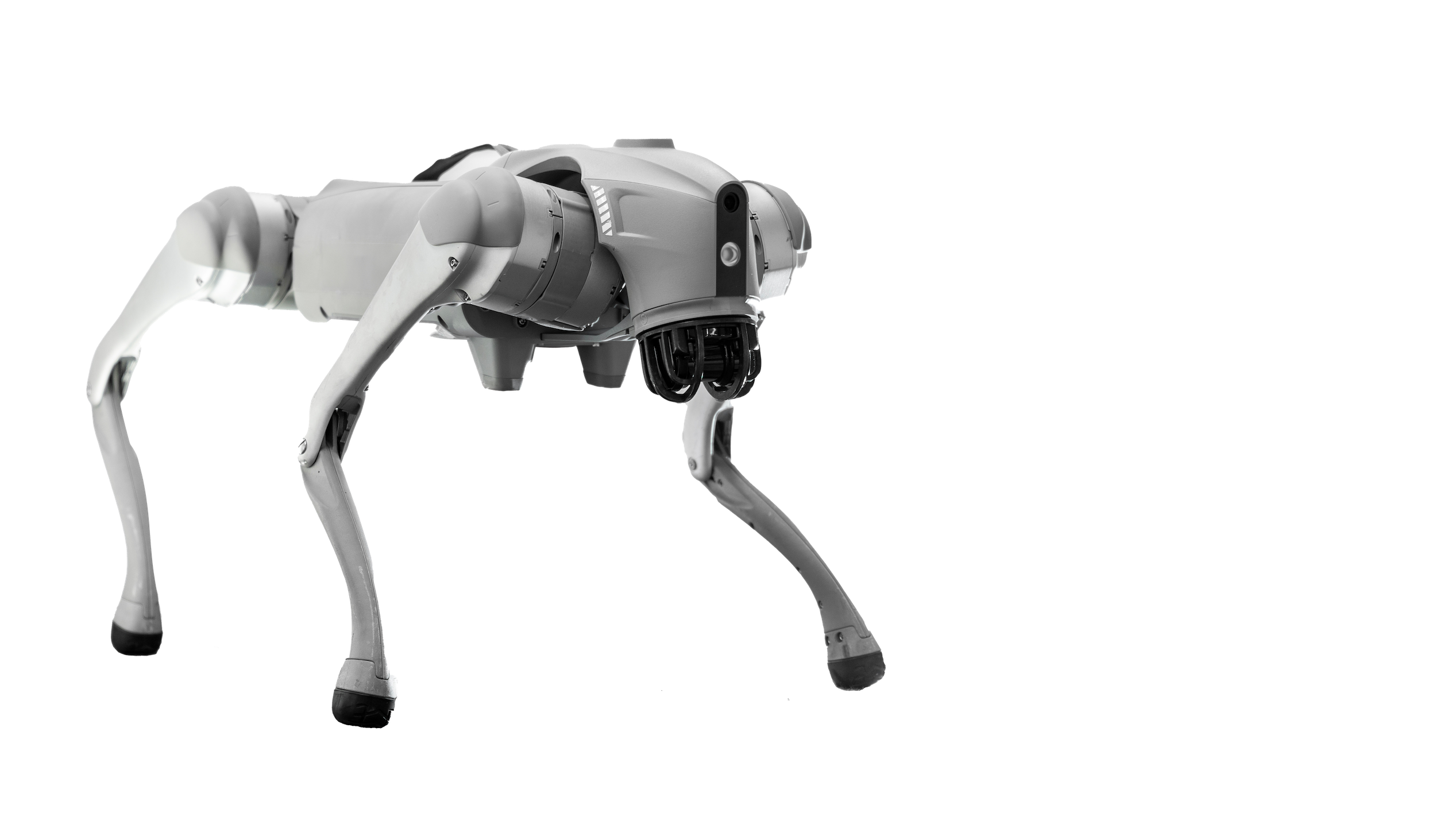

Feng’s lab has pioneered research on fourlegged robots popularly known as robot dogs. The canine-sized devices have exhibited the ability to traverse many types of terrain and have been used to aid search efforts and survey sites after natural disasters. By outfitting these mechanical mutts with sensors and cameras, the robots could collect data on vegetation growth and environmental conditions in areas prone to wildfires. Once the data is collected, it could be analyzed by an AI program trained to pinpoint fire risks.

Right now, robot dogs still need a human companion to control their movements. But Feng envisions automating these robots to move through the environment like self-driving cars. His lab is currently working on machine learning algorithms and plans to have a robot dog eventually walk itself to their collaborators across town at Columbia University.

Feng estimates that robot dogs will be able to autonomously maneuver through fire-prone environments within three to five years. He thinks that developing the AI algorithms needed to process the wealth of data collected by drones and robots that detect, early and reliably, fire hazard risks for first responders will likely take longer and will depend on investment from the government and buy-in from a society that can be wary of the benefits of AI. “AI isn’t just about creating funny images,” Feng said. “We want to use AI and robotics to do good for society.”

Feng and the other BRAHMA team members emphasize that automating robot dogs and other devices is meant to support, not replace, human firefighters. According to Miura, “automation will not fully replace human expertise, but it can serve as a critical force multiplier, giving communities more time and better information to respond effectively as well as save firefighter lives.”

Supporting the Firefighters

BRAHMA is not the only research team at NYU automating fire safety. For the past 20 years, NYU’s Fire Research Group, led by principal investigator Sunil Kumar, a Global Network Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Tandon (as well as a professor at NYU Abu Dhabi), and Research Associate Professor Prabodh Panindre (MAE), have utilized technology to revolutionize firefighting procedures and translate fire research into real-life practices.

Early on, the Fire Research Group used experimental fires set in an abandoned highrise on Governor’s Island to understand why fires in apartment buildings turned deadly. Their discoveries yielded several firefighting breakthroughs, including specialized positive pressure ventilation fans and wind control devices that can cover the windows of burning rooms, which were quickly adopted by collaborators at the Fire Department of New York City (FDNY) and other fire departments across the country.

Setting apartments ablaze is costly and potentially dangerous. So Kumar and Panindre began crafting scientific simulations of fires. This led to the creation of Advanced Learning through Interactive Visual Environments (ALIVE), an online training program that presents firefighters with a number of firefighting scenarios, including wind-driven and residential infernos, that they could face on the job.

For Kumar, the most important aspect of ALIVE, which has been adopted by over 1,000 fire departments across the country, is disseminating up-to-date information on fire safety science to firefighters. “One of the urgent needs in the fire service is the translation of research,” he said. “Most of the researchers publish their work in scientific journals, but we need to make sure that the end user is also able to use that research.”

Prabodh Panindre has been leading research at NYU’s Fire Research Group alongside Sunil Kumar for the past 20 years.

Prabodh Panindre has been leading research at NYU’s Fire Research Group alongside Sunil Kumar for the past 20 years.

The Fire Research Group also aims to keep firefighters informed in other aspects of their lives, especially when it comes to their health. The team noticed that an alarming number of firefighters died not from burns or smoke inhalation but from cardiovascular diseases. This led the team to develop an AI-based mobile app that monitors a firefighter’s health by connecting to devices like Apple Watches or Fitbits. The app tracks factors like heart rate and sleep patterns and uses an AI model to provide daily insights to improve their health. This even extends to a firefighter’s diet. If they take a picture of their plate, an AI-enabled feature on the app will analyze the nutritional value of their meal.

Their latest effort, published in the IEEE Internet of Things Journal, is developing an AI application to recognize flames in footage captured by security cameras, a widespread and often untapped source of data in urban areas like New York City. The project’s goal is to co-opt these ubiquitous devices to detect fires before they spread. This AI application represents the remarkable evolution in the Fire Research Group’s research work.

“In the beginning, we started by actually burning buildings to help develop firefighting procedures,” said Panindre. “Now we want to take the fire service to the next level by implementing AI and other cutting-edge technologies that they can use to make better decisions.”

When fire is detected, their application automatically generates short video clips and issues instant alerts via email and text message. Because it works with existing CCTV infrastructure, the technology can be deployed at scale without the costly installation of new hardware, a breakthrough that makes widespread adoption far more feasible.

Crucially, the system is not limited to buildings. It can be mounted on drones and unmanned aerial vehicles to scan vast forested areas for signs of wildfire.

“It is a game changer because you can have a drone flying over the wildland continuously that can detect fire or smoke even in remote parts of the forest.”

Early detection buys critical hours in the race to contain wildfires, enabling quicker deployment of firefighters, more efficient use of suppression resources and earlier evacuation orders that save both lives and property.

To improve situational awareness, the same AI can also be embedded directly into the tools firefighters already carry, from helmetmounted cameras to vehicle-mounted systems and autonomous firefighting robots. The Fire Research Group’s long-term goal for this technology is to create a swarm of autonomous aerial vehicles that can scope out the location of a fire and provide firefighters with a 360-degree view of the inferno while they are en route. These drones could also pinpoint where people are trapped in a burning building, providing commanders with real-time intelligence that is otherwise difficult to obtain.

Beyond fire detection, the same approach could be adapted to other emergencies such as security threats or medical crises. By transforming everyday systems with the integration of AI, the Fire Research Group is reshaping the emergency response on multiple fronts, making communities safer, more resilient and better prepared for a wide range of risks.

Feng envisions BRAHMA eventually utilizing a similar approach to analyze visual data collected by satellites orbiting the Earth. And according to Miura, these efforts are only becoming more environments within three to five years. He thinks that developing the AI algorithms needed to process the wealth of data collected by drones and robots that detect, early and reliably, fire hazard risks for first responders will likely take longer and will depend on investment from the government and buy-in from a society that can be wary of the benefits of AI. “AI isn’t just about creating funny images,” Feng said.

A Holistic Approach

The BRAHMA program was initially inspired when a Tandon dean suggested to Guibaud that his research would dovetail nicely with work being conducted by Feng, Miura, and Villalobos. Now the initiative is in the stage of securing funding to begin building comprehensive wildfire risk assessments and eventually train autonomous robots to detect and prevent fires. The next step will also likely include building out BRAHMA’s collaborative approach to include researchers in other NYU engineering programs, including the Fire Research Group.

Miura agrees and thinks that many will realize that seemingly disparate disciplines of engineering often overlap in surprising ways. She was initially drawn to the program because she thought each of the BRAHMA collaborators’ approaches revolved around a central, straightforward goal: mitigate environmental hazards with cutting-edge technologies. “I saw an opportunity to contribute to a team tackling one of the most pressing climate-related challenges of our time,” she said.

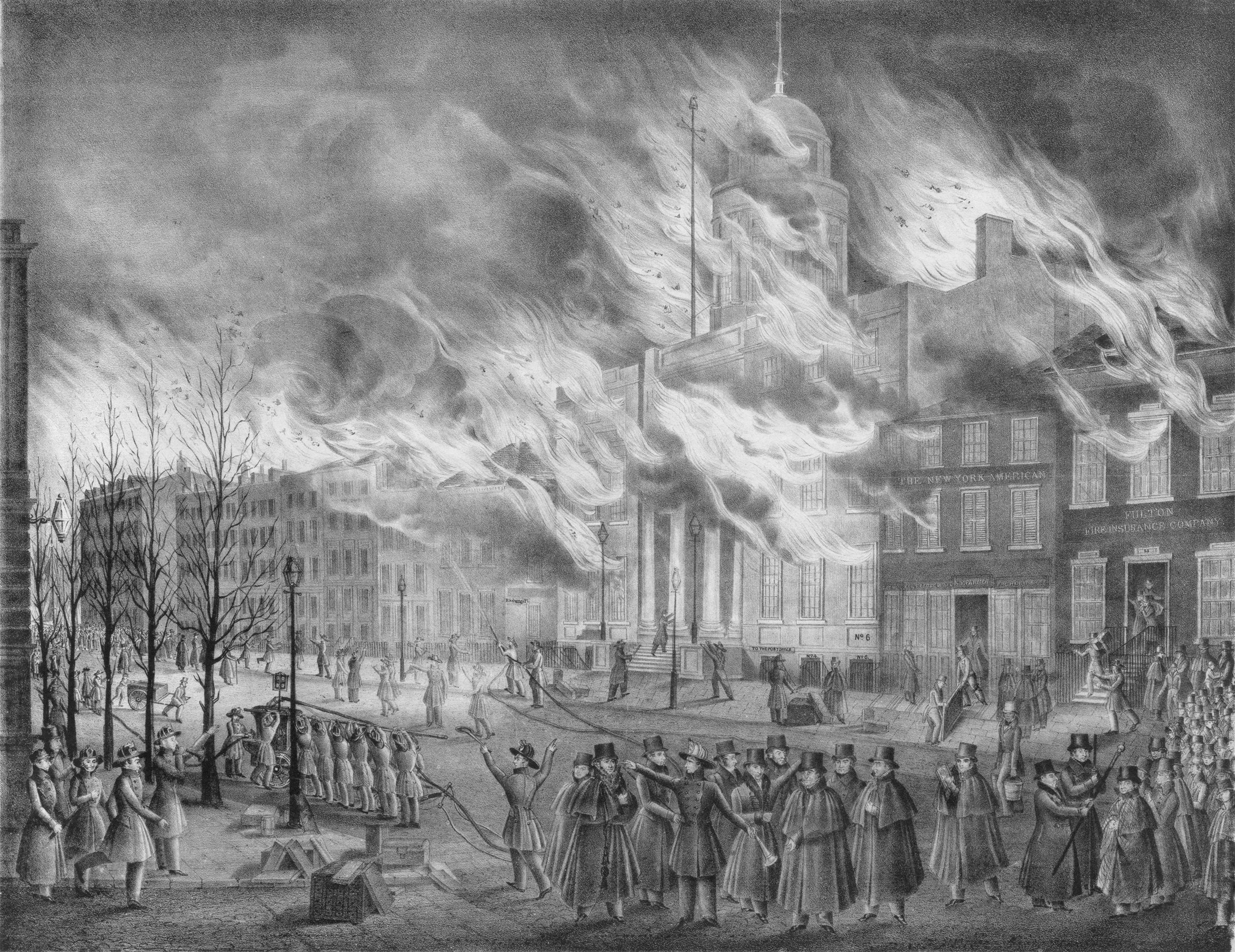

IgNYte-ing New Lab Space

The fact that NYU researchers are calibrating the future of fire safety is fitting because the institution’s home city has been forged by fire for centuries. Just as New York was maturing into a great metropolis, it was beset by a series of destructive blazes. The first occurred in 1776, when a fire scorched a large section of the West Side of Manhattan, which was then occupied by the British. In 1835, another fire tore through lower Manhattan, charring 17 city blocks. Just ten years later, New York’s final “great fire” burned through Manhattan. It started at a whale oil manufacturer and eventually ignited a store of potassium nitrate, a key ingredient in gunpowder. The New York Tribune described the resulting blaze as “an amphitheatre of blood-red flame sweeping like a hurricane on fire.”

While the days of whale oil warehouses and stores of gunpowder sparking great blazes are thankfully in the past, New York City remains a dynamic environment for fire. The city’s diversity of building types, ranging from historic brownstones to sleek high-rises, pose a myriad of fire risks. Densely packing these buildings together and adding combustible devices like electric cars makes the fire risk even more complex.

This environment greatly appealed to Guibaud, as did the ability to work with collaborators in the Fire Research Group and local agencies like the FDNY. In the fall of 2026, IgNYte’s physical lab space will open in Jacobs Hall and become fully operational the following year. “We’re going to be conducting fire experiments in the heart of New York City, which is unique,” Guibaud said.

Many of the lab’s large-scale experiments will be conducted under a giant fire hood— essentially a supersized version of what sits above a kitchen stovetop. The experimental chamber can contain fires up to 500 kilowatts, about five times the strength of a standard campfire, and will allow Guibaud and his colleagues to tweak factors like air flow and fuel type to see how they impact a flame and monitor toxic pollutants in billowing smoke.

The lab’s machinery and advanced optical diagnostics will help guide Guibaud’s research on topics as diverse as flames at zero-gravity or the threats fire poses to New York’s centuryold buildings. It will also eventually help contribute to BRAHMA’s efforts to automate wildfire monitoring and prevention.

Guibaud cannot wait to light the experimental flames and explore questions that have long sparked his research interests. “You sometimes get really into the weeds with all the technical and scientific details needed to understand even a simple candle flame,” he said. “And then you take a step back and remember that you work on a project about putting a box on the moon and setting it on fire. That makes the whole thing seem like what a five-year-old would want to spend their time on.”